The Peak production of cocoons in Japan was around 1930.The rural areas of northern and western Tokyo became influential production areas.

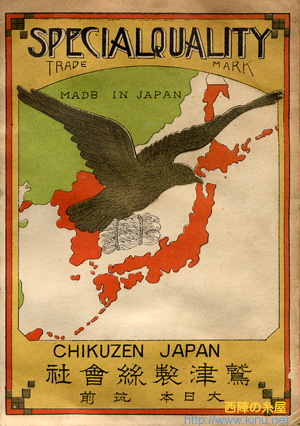

Agrarian society played a critical role in the economic transformation of Meiji(1868-192) Japan. It was a vital source of the labor power, food, tax revenues, and export earnings that made the industrial revolution possible. Until about 1920, Japanese farmers supported the growing population with increased output. It also preserved scarce foreign exchange for imports of industrial and military technologies rather than food. Farmers brought in crucial foreign exchange by exporting tea and silk products.

A silk blight in Europe in 1868 opened the way for a booming export trade in silk cocoons raised in small sheds on family farms. When the European blight ended, the emphasis shifted to exports of silk threads.

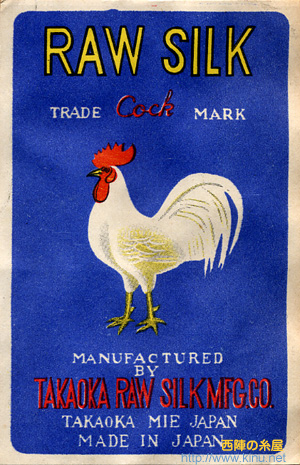

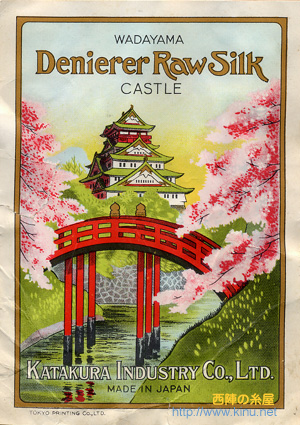

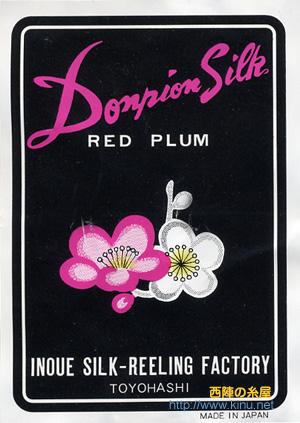

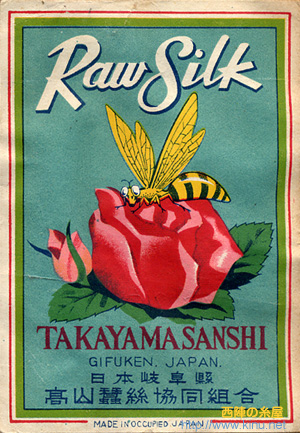

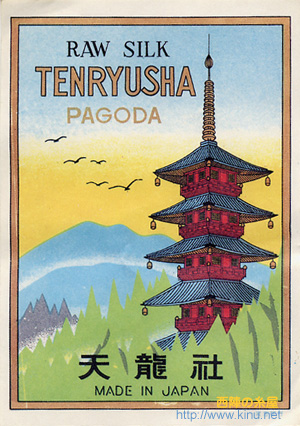

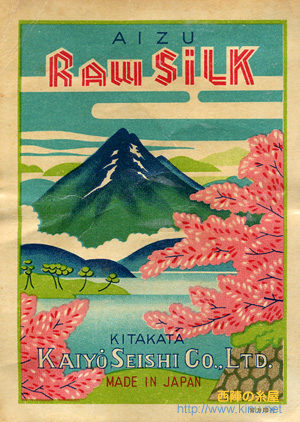

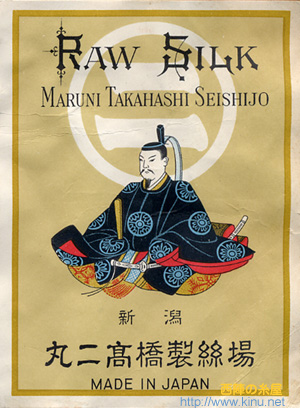

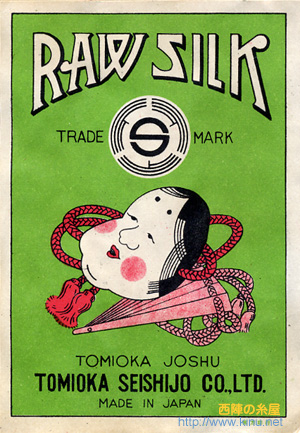

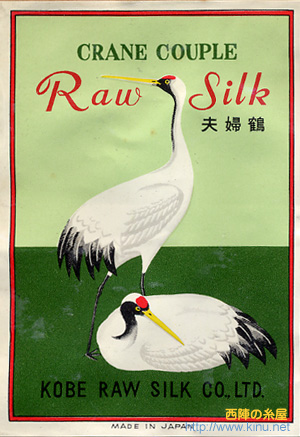

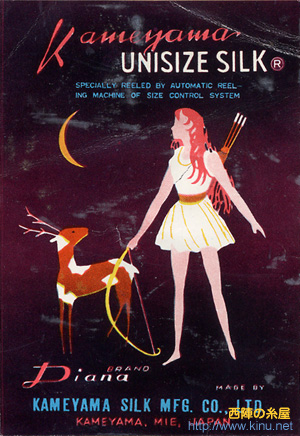

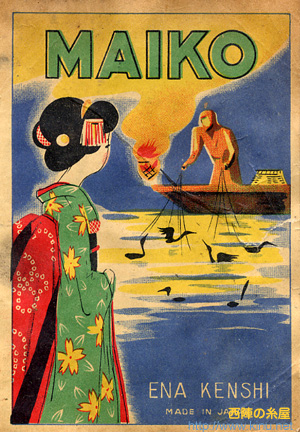

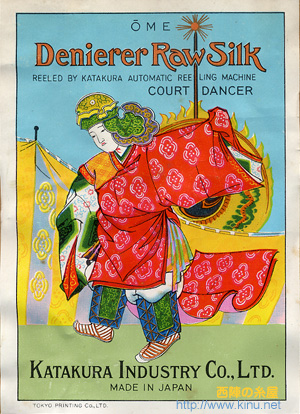

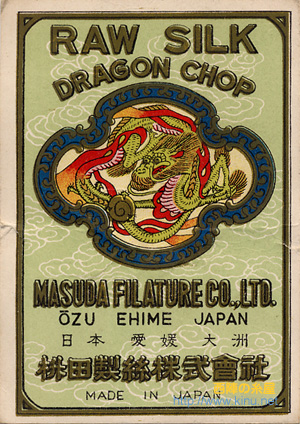

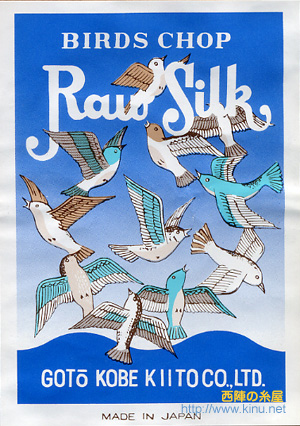

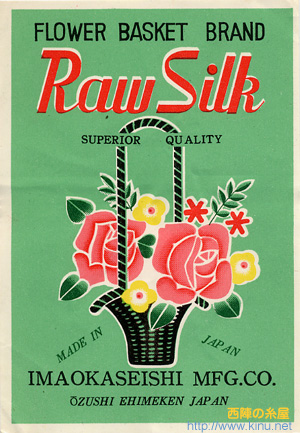

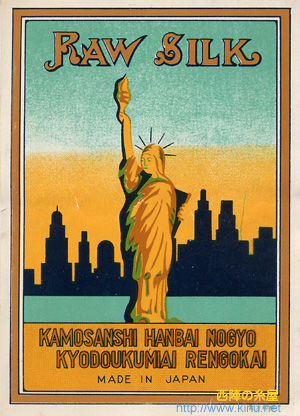

Between 1868 and 1893 Japanese raw silk production rose almost fivefold. Most of this was sold overseas. Silk accounted for 42% of all Japanese export revenues during this quarter-century. The raw silk was brought to Yokohama Port by railroad and exported to Europe and America.

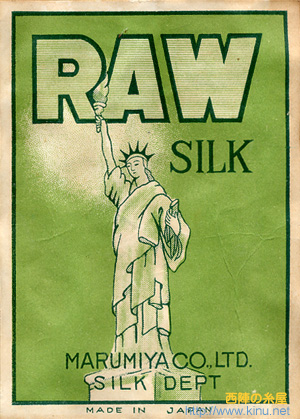

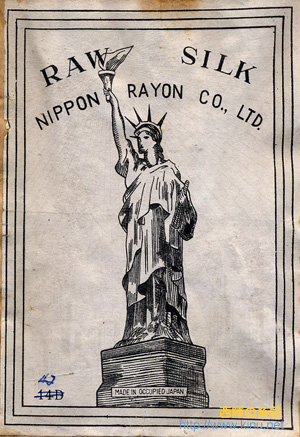

The main export destination changed from Europe at the beginning of the 20th century to the United States, and from the 1920s onwards, most raw silk was sent to the United States. The American silk textile industry, which began to develop in the 1880s, surpassed Europe in production volume in the 20th century and came to dominate the domestic American market. Furthermore, in the 1920s after World War I, there was a change in fashion design, and the production of women’s stockings increased sharply, with 70 to 80 percent of raw silk being used for this purpose.

The American silk weaving industry, which chose Asia as its source of raw materials from around 1890. The transcontinental railroad, which opened in 1876, brought about a major turning point for the American silk industry. With this opening, raw silk, which had previously been transported nearly three-quarters of the way around the globe, could now be obtained from Asia, the world’s largest producer, in just one-third of the way around the globe. Most of Asia’s raw silk was exported by Japan and China.

The opening of the US transcontinental railroads brought change to these stagnant Pacific routes. Following the opening of the New York-San Francisco line, transcontinental lines were laid one after another in the south and then the north, and in 1887, the Canadian Pacific Railway of Canada extended its line to Vancouver on the Pacific coast. Japanese shipping companies also began to open regular transpacific routes, and in 1896, Nippon Yusen opened a Yokohama-Seattle route, linking up with the Great Northern Railway, a US transcontinental railroad company.

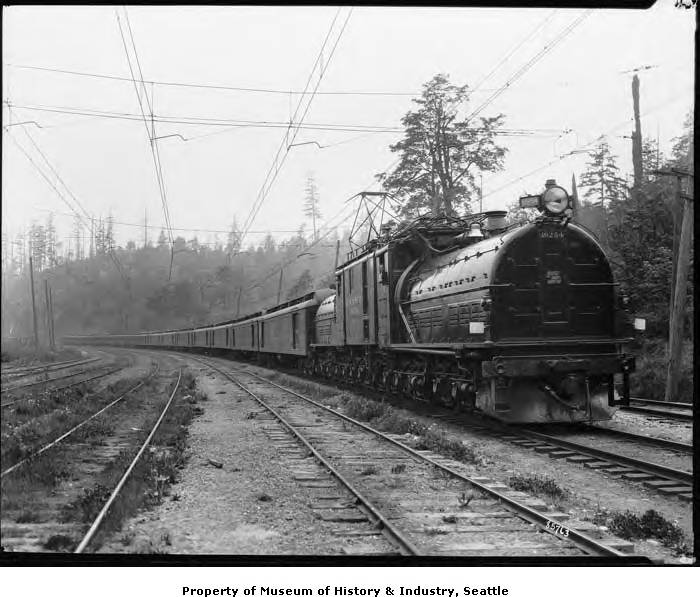

The silk train was an express freight train that transported raw silk from ports on the Pacific coast such as San Francisco to the suburbs of New York, where textile manufacturers were based. This was because raw silk was extremely expensive. For this reason, transportation insurance was necessary for large quantities of raw silk. Importers therefore wanted a route that could shorten the transportation time by even an hour, and railroad companies responded by speeding up silk trains.

Most of the raw silk bound for New York, the largest destination of silk trains. In America, most silk-related factories were located around New York City, and one of the reasons for this is said to be that banks, financial institutions, and wholesale companies with experience in commodity trade with Asia were concentrated in New York City. Silk fabrics in America were for the general public, and the main products were women’s dress fabric and later mid-range products such as stockings, scarves, and men’s shirts and handkerchiefs, as well as ribbon fabric and sewing thread.

PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; All Rights Reserved

The production of silk stockings expanded rapidly from the 1920s onwards. In the 1920s, the amount of raw silk used was at most 20-30%, but it increased year by year, and by the early 1940s, 70-80% of imported raw silk was consumed in the production of silk stockings. This was due to the social background of the fashion for short skirts after World War I, the high wages in the United States that made it possible to spend money on silk stockings, which are relatively expensive and a consumable item, and the fact that women who entered the workforce needed clothing that was somewhat fashionable.

I have traced the “Modern Silk Road” from Yokohama Port to the West Coast of the United States and then to New York, but now let me turn my attention once again from Yokohama Port to the northern area of Tokyo.

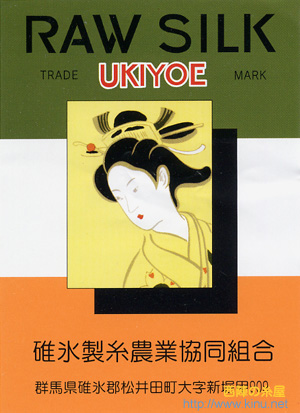

The production districts of Meisen were Ashikaga, Isesaki, Chichibu and Hachioji in those rural areas. Isesaki and Ashikaga in Gunma was a major production area of Japanese raw silk from the middle of the 19th century. Between Ashikaga and Isesaki, there is a city ,Kiryu. It was a large production area of silk fabrics before the 19th century and there was a huge consuming area, Edo (Tokyo) in the south. Rural villages in the neighborhood bred the silkworm as a side job. Kiryu produced luxury goods, Ashikaga and Isesaki produced for the masses. An industrial map was formed.